New Year's Eve is always a time for parties, but some years there's a special reason for extra celebration.

The end of a decade or a century, for example. Or - as was the case 24 years ago - the end of a millennium.

You'd think witnessing an event that occurs only once every thousand years would be cause for great joy, but as the end of the 20th Century approached, the media and the public became increasingly focused on a potential computer glitch that some people believed would lead to worldwide disaster as the new millennium began.

(Yes, the new millennium technically began on Jan. 1, 2001, not 2000. But the voice of the masses - and of computers - was not to be ignored. And aren't all measurements of time arbitrary, anyway?)

The Y2K bug, as it came to be called, was a result of the economy of language required by early computer systems, in which memory was sorely lacking.

Programmers would use only the final two digits of a four-digit year; 1999 was "99," for example. This meant that the year 2000 was indistinguishable from the year 1900 - and the large-scale effects of that computer confusion were unknown.

Globally, fixing the Y2K problem was a years-long process that cost hundreds of billions of dollars. Y2K was also a source of panic and fear, as people stockpiled supplies and fringe religious groups prophesied the end of civilization.

But what did it look like in Lancaster County?

Here's what we found in the LNP | LancasterOnline digital archives.

Lancaster city prepared a large number of temporary stop signs in case the Y2K glitch caused traffic lights to go out.

The first mention of a potential computer problem associated with the year 2000 was in the Intelligencer Journal of Jan. 22, 1996. That article, reprinted from the Christian Science Monitor, described various theoretical situations that might happen thanks to the glitch, as well as some that already had occurred.

For example: If you were born in 1982 and applied for a driver's license in 2000, would the state computer think you were 18 or 82?

A bank had already been hit by the glitch, finding that interest checks for seven-year bonds coming due in 2000 were being issued for millions of dollars more than they should have been - because the bank's computer system read "00" as "1900."

By June of the next year, local articles began to discuss the issue. This story in the Sunday News business section mentions the fact that programmers who knew archaic computer languages such as FORTRAN or COBOL were suddenly in demand again - at salaries two to three times what they had previously been earning.

In August 1997, the first of countless articles about how municipal officials would address Y2K appeared. Lancaster city had hired a consulting firm to determine whether it should buy all new computer software or update the existing programs, which were 25-year-old COBOL systems.

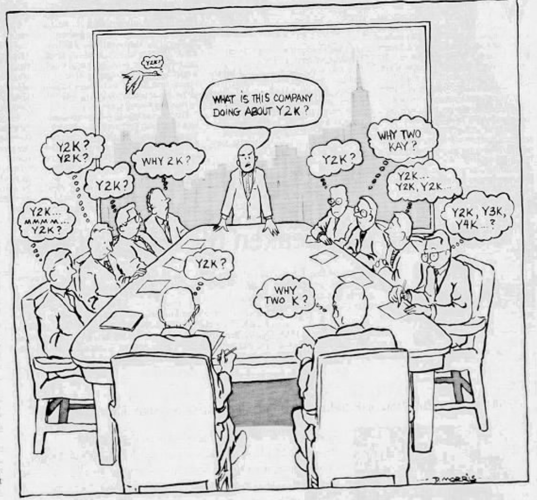

This cartoon appeared on the cover of Lancaster Newpapers' Business Monday tabloid in February 1998.

As 1998 dawned, focus on the Y2K bug started ramping up. A roundup of what local school districts were doing to address the problem appeared on the front page of the Intelligencer Journal on Jan. 9, and Y2K was the cover story of the Business Monday tabloid on Feb. 2.

That Business Monday story addressed not only the problems that local businesses might face in the year 2000, but also the opportunities for computer firms and consultants to capitalize on Y2K.

Looking back, a big part of the media's early Y2K coverage was focused on uncertainty. Was this actually going to be a problem, or was it tech-sector hype? Would it be just some minor errors on people's paychecks or utility bills, or would airplanes fall out of the sky while power grids shut down?

Editorials took a slightly bemused tone, somewhere between jokes and worry, and letters to the editor began to express significant fears.

The Lancaster Chamber of Commerce & Industry, meanwhile, was offering seminars for business owners about preparing for the year 2000, and made the Y2K bug a main focus of the 17th annual Business Expo and Conference in October 1998. Law firms discussed the possibility of lawsuits arising from unprepared businesses, and consultants offered to test computer systems to see what they would do faced with that unprecedented "00" date.

The next month, the Sunday News ran a front-page story about how some conservative Christians were taking the Y2K bug as a sign of the end times, and preparing accordingly.

Dennis Herr of E.M. Herr Farm & Home Supply in Willow Street stocks his store with generators and kerosene heaters in this photo from Feb. 1999. Such products were in high demand in the run-up to the year 2000, as people believed the Y2K computer bug would knock out power and other utilities.

"Conservative Christians are far more aware of Y2K than society in general," the article states. "The issue has been covered extensively in Christian media and many prominent commentators have urged the faithful to prepare for what might happen if and when the computers die."

There was a nationwide surge of interest in "survival" materials - generators, canned and freeze-dried foods, bottled water - largely driven by Christians spurred to action by local pastors, televangelists and conservative Christian websites.

Meanwhile, Lancaster city had finished with its consultants, who ended up changing a half-million lines of code in computer systems that governed everything from water and sewer bills to parking tickets to payroll.

In January 1999 - less than a year from the Y2K deadline - many small businesses still were ill-prepared, while people shopping for home computers wanted their computers to be Y2K compliant, but many had no idea exactly what that meant.

And nearby nuclear power plants at Three Mile Island and Peach Bottom were reassuring residents that they would be ready for Y2K - the power would stay on and the plants would be safe.

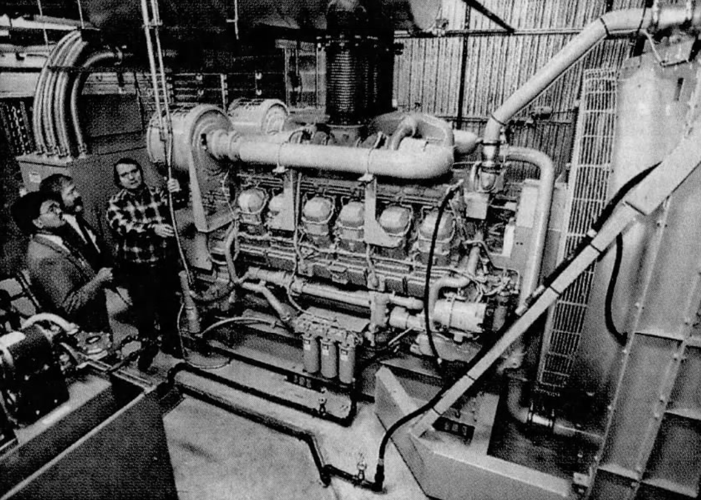

Lancaster General Hospital added this backup generator to keep medical equipment running in the event of massive power outages due to the Y2K computer bug.

The next month, as reports indicated that a whopping 30 percent of Americans were stockpiling for Y2K, the wariness and concern among county residents was increasing - but still falling short of outright panic, at least for most people.

Local pastors were advising parishioners to prepare for "disruption" of their lives, but not the apocalypse. Treat Y2K, many said, like a major storm or other natural disaster - lay in a supply of food and water, maybe buy a generator or battery-powered heater if the power goes out for an extended period.

But some retailers around the county were sold out of generators and heaters, with one shop owner saying her customers were a mix of people who wanted to stockpile for Y2K and people who were doing nothing because they believed "the world is going to end because God is going to come."

And one county locksmith was advertising "Y2K safes" which were proof against both fire and burglars - presumably suitable for protecting one's valuables after the fall of civilization.

Meanwhile, larger-scale preparations were continuing at a brisk pace, with Y2K updates a frequent presence in newspaper pages. By March, local businesses had already spent millions on the fix but were still unsure if it was enough.

In what was the largest Y2K-related issue in a nuclear power plant to date, Y2K testing at Peach Bottom caused the reactor to lose all its plant-monitoring computers for a period of seven hours. (Backup systems were in place, officials were quick to state.)

Educators Mutual Life employees, who worked for months on upgrading the company's computer systems to be Y2K compliant, celebrate the end of the project with a beach party in downtown Lancaster in this photo from September 1999. The empty plot of land at the corner of Prince and Chestnut streets, opposite Pennsylvania College of Art & Design, was converted to a sandy beach for the day.

There were lighter moments in the torrent of Y2K news, of course. Stoudt's Brewery made a Y2K IPA for the summer season. An insurance company celebrated the end of their Y2K upgrade with a downtown "beach party" for the 220 employees who worked evenings and weekends through the summer to get the company ready.

And the New Era printed detailed instructions for figuring out whether your VCR would still work.

In May, Lancaster General Hospital announced that after spending $13 million to upgrade or replace computers and other equipment, the organization was completely prepared for any potential Y2K troubles.

But, like other local hospitals, they were still stockpiling medicine and other supplies, in case the suppliers of those items were unable to deliver them.

By midsummer, the city, county and state all had announced that their systems would be fully Y2K compliant.

Turning their attention to boroughs and townships, county officials in July revealed a Y2K Action Plan that required all municipalities in the county to evaluate their systems, equipment and vendors and address any potential problems.

As the end of the year drew near, municipalities all over the county hosted meetings where residents could learn how to plan and prepare for Y2K - and bring their questions to representatives of the Lancaster County Y2K Task Force.

Lancaster Countywide Communications Center employees Richard Harrison, left, and Troy Hatfield check computer systems for Y2K compliance in this photo from December 1999.

Starting on Nov. 30, both daily newspapers - the Lancaster New Era and the Intelligencer Journal - published a series of stories about Y2K readiness, starting with an 80-item "Y2K preparation checklist."

Then, over the course of the final month of 1999, the newspapers checked in with various government and private-sector organizations to assess how ready the county was for Y2K.

The 911 system was ready.

Public transportation was ready.

Area hospitals and nursing homes were ready.

Utilities were ready.

Industry. Retail. Grocery stores. Banks. Pharmacies. Schools. All were ready.

There was even a story assuring readers that Lancaster Newspapers was ready, and the papers would be printed and delivered on Jan. 1, no matter the state of the world.

And with that, the long media run-up to Y2K was over.

There was one last warning on Dec. 29 telling readers to stay off the phone around midnight on New Year's Eve to avoid overloading the telephone lines, and then everyone waited breathlessly - some excited, some nervous - for the year 2000 to arrive.

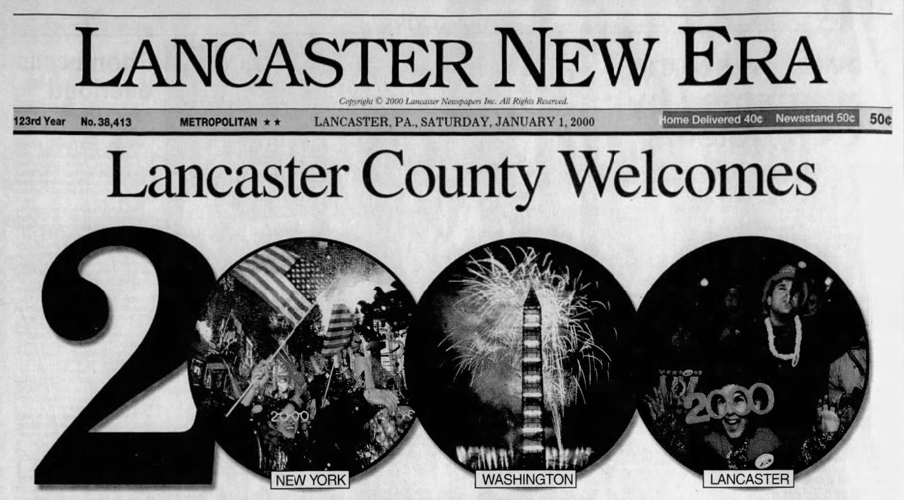

The front page of the New Era from Dec. 31, 1999.

And the next day ... it turned out everything was fine.

The Intelligencer Journal of Jan. 1, 2000, which went to press well before midnight, had a final roundup of preparation - reports of packed grocery stores as people prepared for both parties and power outages, and check-ins with emergency services, where "rumor hotlines" had been set up to field the last of the Y2K-related phone calls.

On the afternoon of Jan. 1, the New Era hit the streets, with the final word on Y2K: "Y2K glitches are no-shows; county officials are relieved," the headline read.

It was over. Years of preparation and media coverage; months of public worry, doubt and speculation; days of last-minute waiting. All over.

People immediately began debating whether the whole thing had been a case of panicked over-preparation for a non-event or, like county emergency management coordinator Randall Gockley put it, "All the preparation has paid off."

The truth, probably, lies somewhere in between.

Surely those millions of lines of computer code would've done something if they hadn't been altered, right?

JED REINERT | Digital Staff

JED REINERT | Digital Staff